Pottery, Souls, Floods and the creation of the world all connect the subject of my blog this week, the ram-headed God Khnum ‘Potter of Mankind’ and ‘Lord of the Cataract’.

Appearance

Khnum has been worshipped early on in ancient Egyptian history from the 1st Dynasty onwards until well into the Graeco- Roman period. Khnum is a ram-headed God with his principal cults on the island of Elephantine at Aswan where he formed a triad with two other goddesses Satet and Anuket[1]. The area around Elephantine and modern-day Aswan is referred to as the first cataract which is an area of rocky rapids on the southern border of Egypt[2]. “His name derives from the root Khnum, “to join, to unite,” and with Khnum, “to build”; astronomically the name refers to the “conjunction” of the sun and moon at stared seasons of the year, Khnum was the ‘Father of Fathers and the Mother of Mothers’ of the pharaoh”[3]. Khnum is generally shown in anthropomorphic form as a ram-headed man wearing a short kilt and tripartite wig. Early depictions of him showed him as having the ram horns belonging to Ovis Longipes, believed to be the first type of ram domesticated in Egypt, which had corkscrew horns extending out horizontally from its head.[4] The earliest depictions of sheep in Egypt come from rock drawings of wild barbary sheep in southern Egypt and Lower Nubia and date to the Neolithic or early predynastic period[5]. Again, the oldest type of sheep is Ovis Longpipes palaeoaegyptiacus which Khnums horns are based upon (Figure 1). Unlike the Ovis platyura aegyptiaca which had horns which curled downs keeping close to the head that became associated with the God Amun[6] (Figure 2). Although, over time, Khnum began to be depicted with both types of ram horns and has two sets of horns on his head and a tall plumed headdress[7] (Figure 3).

The Nile Inundation

Khnum was thought by the ancient Egyptians to control the annual inundation of the Nile, a pivotal point in the calendar, and further embodied the dangerous and life-giving aspect of this flood[8]. A failed flood would spell disaster for Egypt both practically with regards to agriculture and spiritually as the laws of Maat would be uprooted. At Esna his watery connections were furthered with his pairing with Neith as he is sometimes referred to as ‘Lord of the Crocodiles’ as Neith was mother to the chief crocodile god Sobek[9]. But Khnum’s main temple is found on the island of Elephantine (Figure 4).

The so-called famine stela shows the height of Khnum’s connection to the flooding of the Nile (Figure 5). The Famine stela refers to an inscription located on Shel Island neat Aswan and tell the tale of how king Djoser brought to an end a 7-year long famine and was inscribed into a natural granite block whose surface was cut into the rectangular shape of a stela written in hieroglyphs and contains 42 columns[10]. The inscription talks of a decree of king Djoser who rules 2667-2648 but was actually composed about 2,500 years later than his reign[11]. The 7-year feminine was brought about because the Nile did not flood. In order to rectify the situation, Djoser summons the wisest priests who could read the sacred texts in an effort to locate the source of the inundation[12]. This portion reads – “Everyone was in distress. I consulted one of the staff of the Ibis, the Chief lector-priest of Imhotep, son of Ptah South-of-the-Wall. He departed, then returned to me quickly, He let me know the flow of Hapy” Hapy being the personification of the Nile itself.[13] Then a priest named Imhotep reveals to Djoser that the Nile’s source had its origins in a land consecrated to Khnum and gave an account of the building materials available at Elephantine[14]. The source more specifically came from Twin caverns under the Island of Elephantine and that Khnum had the power to unbolt the doors and release the flood[15]. Khnum then appeared to Djoser in a dream with the promise to end the drought and described how a temple should be built. Grateful, Djoser re-established the cult of Khnum at Elephantine and the famine was then ended.

Potter of Mankind

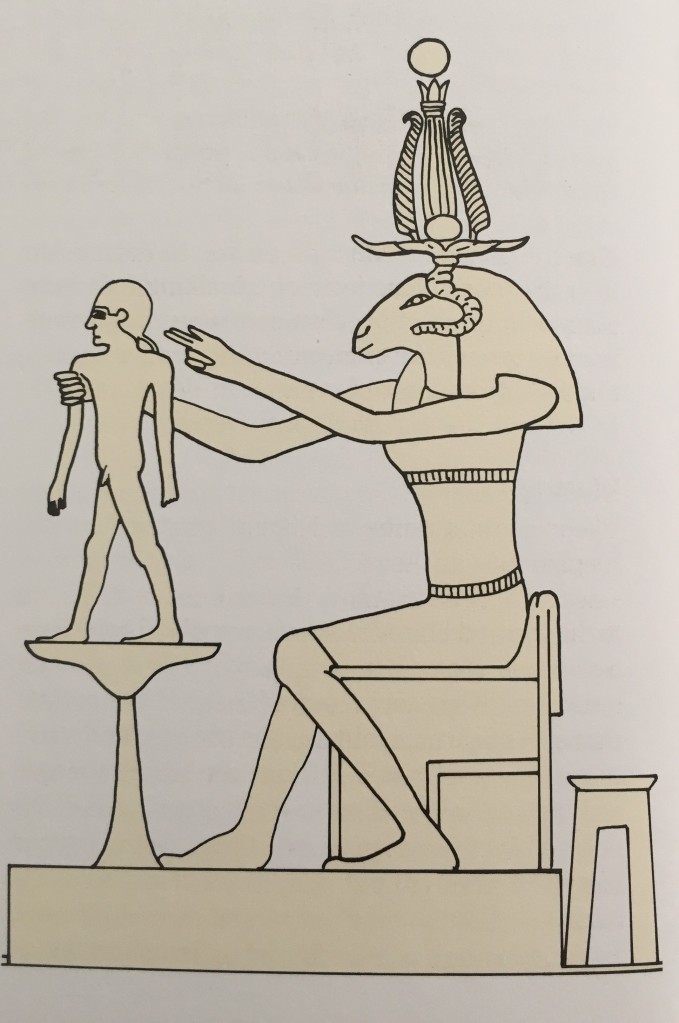

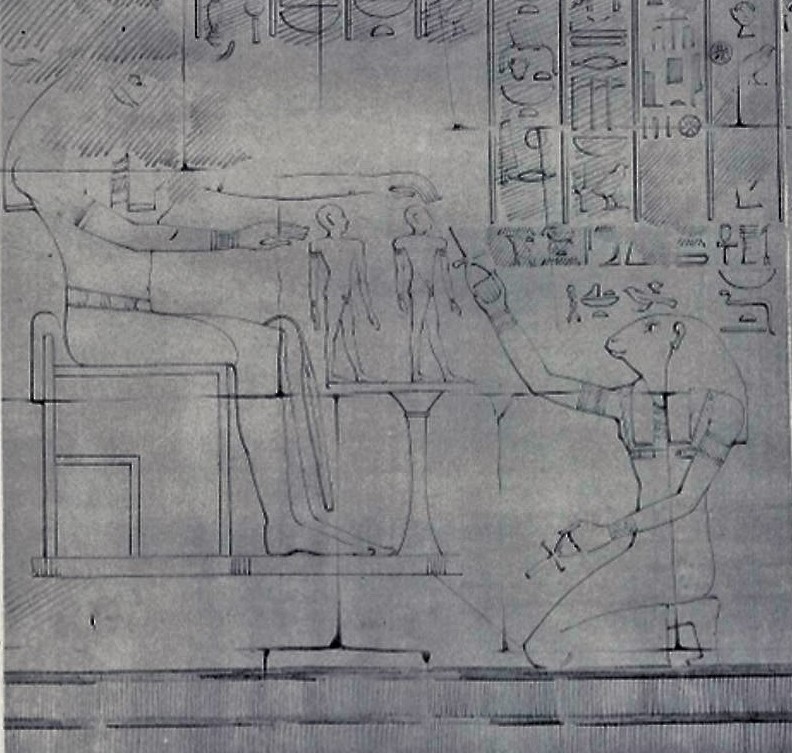

Khnum’ strong association with the Nile inundation and by extension its fertile soil itself contributed to his role as a potter god and led to his cosmic role as one of the principal creator gods alongside Ra, Atum and Ptah. His role as a creator god stemmed from the combination of the creative symbolism of moulding pottery, the traditional potency of the ram and the fact that the Egyptian word for Ram Ba also had the meaning of spiritual essence[16]. In the mythology surrounding Khnum and creation, he is said to have shaped people, animals and plants on his potter’s wheel and put life and health into their bodies[17]. In both the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts Khnum is mainly written about creating boats however in the Old Kingdom Khnum formed part of a group of deities that came to Egypt in disguise to assist with the birth of three children all destined to be king[18]. In this tale Khnum makes their bodies health with scenes showing him making the royal body and its ka or double in his potter’s wheel[19]. All of this seems to take place in the celestial realm as an intrinsic part of the prelude to the king’s physical birth (Figures 6 and 7 Hatshepsut). In temples of the first millennium, the births of the gods were celebrated in similar scenes to that of kings. Khnum created animals and the physical forms of these baby gods starting with the shaping of the egg in the womb[20]. Furthermore, the idea of Khnum moulding children motif was naturally utilized in birth houses, sometimes referred to as Mammisi, of temples[21]. At the Roman period Temple of Esna Khnums’s role as the maker of bodies was celebrated at the ‘Festival of the Potter’s Wheel’. At this festival, hymns were sung praising ‘the lord of the wheel’ the one ‘who fashioned gods and men’ with his wheel being spun to remake the cosmos every morning.[22]

I hope you have enjoyed this dive into the workings of Khnum’s potter’s wheel and how he held the power to release the flood waters of the Nile.

References

[1] Shaw, I. and Nicholson, P., 2008. The British Museum Dictionary Of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. Page 169

[2] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 153

[3] https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/khnum/

[4] Shaw, I. and Nicholson, P., 2008. The British Museum Dictionary Of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. Page 169

[5] Nicholson, P. and Shaw, I., 2009. Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Page 269

[6] Nicholson, P. and Shaw, I., 2009. Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Page 269

[7] Wilkinson, R., 2007. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson Page 194

[8] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 153

[9] Wilkinson, R., 2007. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson Page 194

[10] https://madainproject.com/famine_stela

[11] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 154

[12] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 154

[13] http://www.touregypt.net/faminestele.htm

[14] http://www.touregypt.net/faminestele.htm

[15] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 154

[16] Shaw, I. and Nicholson, P., 2008. The British Museum Dictionary Of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. Page 169

[17] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 153

[18] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 153

[19] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 153

[20] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 154

[21] Wilkinson, R., 2007. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson Page 194

[22] Pinch, G., 2004. Egyptian mythology A guide to the Gods and Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press. Page 154

1 thought on “Khnum – Potter of Mankind”